Chetco Bar Fire Series: When Wildfire Raced Toward Our Schools

When wildfire raced toward our schools: Evacuations, school delays, air quality concerns and putting the community first

Recollections of the Chetco Bar Fire from Superintendent Sean Gallagher, Brookings-Harbor School District 17C

On the long drive home from a regional superintendent’s meeting in mid-August 2017, Superintendent Sean Gallagher’s cell phone began to ring nonstop. “I had to pull over multiple times to take urgent calls,” he recalled.

A dire situation was developing. As he raced toward home on Highway 101, an inferno was exploding toward the community of Brookings-Harbor.

The Chetco Bar Fire, which had simmered for more than a month deep in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness with little notoriety, had suddenly exploded in size due to strong hot, dry and windy weather conditions known locally as the “Chetco Effect.” What had been 20 miles away, was quickly encroaching on town — cutting the separation to 5 miles — jumping ridges and gobbling more than 100 square miles of dense forest and vegetation along the way.

By the time Supt. Gallagher reached home, an apocalyptic cloud of smoke covered the quaint beach town and harbor — with a pall extending far out over the Pacific Ocean. Burning leaves and ash rained down. Evacuation orders were updating hourly as residents living upriver and in the hills above town were urged to leave immediately (Level 3 – Go!).

Ultimately, the firestorm would bring fear, excitement, long-term evacuations and many needed adjustments for the school district. In the coming days, the schools would serve as a Red Cross Emergency Shelter, the home of a major incident command fire camp with 500 personnel staying on the school grounds, host to numerous community fire information meetings and even a press conference for Oregon Gov. Kate Brown.

Image: Fire team tents filled athletics fields at the Brookings-Harbor School District in August 2017. More than 1,000 personnel for wildland and structural fire crews representing nearly every town and county in Oregon and other communities across the West drove through the night to reach Brookings in time as the fire exploded in size during the August 18-23 weekend, just before the 2017 total solar eclipse. They stayed for weeks to months, establishing three major fire camps. (Nancy Raskauskas-Coons/BHSD 17C)

Incident Command Meetings

Gallagher recalled, that by the time he arrived in Brookings that day, the Red Cross had already set up a shelter on school district property and supplies were starting to roll in. The school district is an emergency management center for the Brookings-Harbor community where Red Cross or emergency services can use the facilities in the event of a fire, tsunami, earthquake or other natural disaster.

Soon the town was filled with wildland fire crews and structural fire crews from all across the state and nation — an impressive amount of organizations and resources to keep track of and coordinate.

“Looking back, if I could pick out one key decision that helped guide our schools through the situation that unfolded, it was the opportunity to be part of daily unified command meetings about fire operations. I woke early and attended these briefings each morning, and was sometimes called to urgent or emergency briefings during the day,” Gallagher said.

The incident command meetings involved representatives from local emergency management services, city, county, state, and federal agencies.

“Everyday was a new day, a new twist, and being in the room with the fire command kept me in the loop with the most current information. I would meet with our school administration and directors team immediately after to share out the information. This advance intel helped us to make the right decisions as we grappled with a situation no textbook or staff training had prepared us for. It is amazing what a unified team can accomplish together in the best interest of our students and the community,” Gallagher reflected.

During the uncertain early days of the fire calamity, Gallagher and the school district leaders focused on their purpose as a public school district to first educate students, while recognizing that sometimes providing support to the overall community takes priority as the way to best support these educational goals.

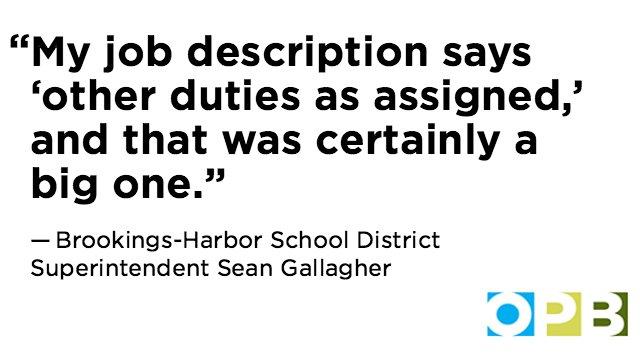

“‘Other duties as assigned’ was the phrase that comes to mind as I reflect upon this moment for all involved — there were important roles and tasks that needed to be filled and accomplished,” Gallagher said.

The Multiple Roles of a School District

On the day the fire erupted, and people began to be displaced, a Red Cross Emergency shelter was set up on school grounds. However, within 24 hours, the Red Cross elected to move the shelter north to the community of Gold Beach, 30 miles up the coast due to concerns that Brookings and Harbor proper might be in eminent danger.

At this point, the event became very real. Gallagher began to grow concerned for the ability to function as a school district to support the community. “I remember spending a night at my house dealing with smoking embers falling out of the sky on my house, yard, and street,” he said.

Even with that threat, the school grounds were still one of the best areas available as a staging ground for the initial fire camp with its large open area and the ability to park EMS vehicles, pitch tents, and take showers. The district provided conference call communications rooms, centralized command facilities, bedding centers, shower facilities, and transportation shuttles to food service staging areas that fed the firefighters twice a day. The other half of the firefighters that initially surged into the community set up in the parking lots of the harbor and marina.

Gallagher found himself helping to manage and run a fire camp in coordination with State Fire Marshall, who he said did an outstanding job of maintaining their own operations including communications, coordination, and outreach.

The firefighters that the district hosted on campus were professional and polite – great role models for students, according to Gallagher. Many of them told the Superintendent that they would be returning someday to vacation in Brookings once this fire event was over — They had no idea that this beautiful portion of the Oregon Coast existed before the fire event.

“The camp was quiet, everyone was cordial and appreciative for their sleeping quarters with pitched tents on the football field, cots in the sports center, and clean shower facilities, I was constantly watching where I stepped outside our office, it was easy to trip over a firefighter crashed out on the sidewalk, exhausted from their shift. These heroes were putting in Herculean efforts for our community,” Gallagher said.

This fire had Brookings in its sights, and it wasn’t relenting. By this time, for two days the fire had traveled five miles per day towards Brookings, and one more day of similar conditions would have brought this fire directly upon the community. Fire crews were digging lines and preparing houses around the clock.

The Need to Communicate

Image: Brookings-Harbor School District Superintendent Sean Gallagher was interviewed live on Oregon Public Broadcasting’s “Think Out Loud” and by numerous other media outlets during the Chetco Bar Fire. Credit: OPB on Twitter.

“When an event of this magnitude occurs in any community, one’s ability to maintain a focus on educating students changes. Safety of students, staff, community, and district facilities that allow one to create safe space becomes a priority. When people know that the local school district is responding to an emergency event 24/7, decisions are being made in the best interests of students, and the district is responding to community concerns; it creates an element of calm during a situation that is very unsettling and produces extreme anxieties and potential trauma,” Gallagher said.

“Personally I am of the opinion that one can’t ‘over’ communicate during these types of situations. Our district kept track of requests from news sources and made key people available to share information. We wrote, updated and maintained consistent talking points related to our key messages that were repeated frequently, in line with our district goals, and purpose,” Gallagher said.

During the event, the school district facilities hosted multiple public information events led by the forest service and other responding agencies and even hosted live-streams for those that could not attend.

“As a school district, it is easy to get caught up in the moment and be tempted to act more like an news agency than a school system. This is not the purpose of a school district. Multiple safety related events in my years as a Superintendent has taught me to always be sensitive to topics that may trigger points of emotion and safety that are unexpected and hard to predict. We kept our messages simple, school-related and unembellished, so not to add to community trauma through dramatic fire images or dire predictions,” Gallagher said.

Students and Boosters Give Back

The school district also shared good news via it’s channels, such as BHHS student athletes volunteering to move a major fire camp kitchen to a new location south of Harbor and the generosity of our California neighbors to the south in the Del Norte School District who hosted many home games and sports practices for the teams.

Later on, the Brookings-Harbor athletic boosters and community hosted a large-scale “thank you” dinner of steak and seafood for firefighters and emergency personnel. According to a Curry Coastal Pilot article on Sept. 12, 2017 (link no longer available), approximately 500 pounds of crab and 125 pounds of tri-tip were available, and the first 200 meals for firefighters were free thanks to donations from businesses and individual families. Firefighters were also treated to salad, mashed potatoes and a variety of desserts, including apple pie and raspberry cheesecake. Volunteers helping out at the feed included community members and athletes from the high school’s basketball teams.

The Pilot quoted one firefighter, Glenn Segal, the crew boss of a 20-person hand crew, as saying that it was the first time he had ever seen a community host a “thank you” dinner in his 17 years on the job.

Image: Oregon Gov. Kate Brown leads a press conference on the Chetco Bar Fire from the Brookings-Harbor High School track. (Nancy Raskauskas-Coons/BHSD 17C)

The Start of School

The day for school starting was getting close, and the fire was only 10 percent contained, most of the containment was on the line closest to the northern part of Brookings only three miles away and two ridges to the east. The fire crews hit this portion of the line hard in fear of another “Chetco Effect” which would have blown the fire directly into the city. Fortunately, it never materialized. Evacuation routes were limited for Brookings — going west would end up in the ocean, east was towards the fire — it was either north or south. If this fire flanked the community, evacuation routes could be limited to one, or none.

Shelter in place became a stark reality for those that needed to stay for responsibility reasons. The school district’s admin/directors team even briefly talked about sheltering themselves and their families in the school district if needed. Starting school with staff and students wasn’t even an option at this time — many staff members were evacuated, and a large percentage of them had left the community for locations where they could stay with family members and friends.

These facts, most certainly influenced the district’s decision to delay the start of school by one week. “If we tried to start on time, we would not have had enough staff to properly care for our students and we didn’t even know how many students would be present. However, we recognized that the need existed for those that needed not only educational, but social services, and therefore looked to minimize the delay as much as possible,” Gallagher said.

Evacuation orders surrounded Brookings from mid-August, until mid-September. Anyone living outside of town, which included thousands of homes, were under at least a level 2 evacuation orders, or a level 3, which meant immediate evacuation. Citizens were spray painting phone numbers on the hind haunches of livestock and sending them to be boarded elsewhere (read more about the livestock evacuation here), those that were able to stay in town with friends and/or relatives were fortunate, others simply left for other communities throughout the Pacific Northwest to stay with family and/or friends. The school district even allowed a few teachers who did not have any family or friends within the community stay in their classrooms. “Sometimes you simply have to bend the rules for the sake of humanity,” Gallagher said.

When school finally resumed a week late, it started the year with 100 percent of our local teachers, staff in students still in a level 1, 2 or 3 evacuation zones, and some students still living in emergency shelters, such as the one at Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation, just south of the Oregon/California border. (Read the story of the Tolowa Dee-Ni Evacuation Center here.)

Air Quality Concerns

The smoke was oppressive throughout the summer. The school district’s Athletics and Activities leadership was making decisions about whether to hold summer practices on a hour-to-hour basis due to the quickly changing air quality. Many practices were moved to Crescent City, California, about a 30-minute bus ride to the south where sea breezes were helping keep the air over their school grounds clearer than in Brookings.

The resumption of school created additional air quality concerns. The school district formulated an air quality team that included the school nurse, athletic director, and public information officer to make the best use of the information available from these sources and direct observations on our campus. The district followed all air quality guidelines published by Oregon Health Authority (OHA) and Oregon Schools Activities Association (OSAA). Notices were sent out to staff when air quality was poor with clear instructions when outdoor recesses and activities must be curtailed or canceled.

Image: Heavy smoke covered the towns of Brookings and Harbor for many days, extending in the fall. (Nancy Raskauskas-Coons/BHSD 17C)

Lasting Impacts

Brookings-Harbor School district ultimately received a waiver from the Oregon State Board of Education for the missed minutes of instructional time due to the delay to the start of the school year caused by the fire emergency. The decision was made in consultation with the local school board and union (the Brookings-Harbor Education Association), and turned out to be the right call to minimize negative impact to the school district and community. The district teachers and staff were held harmless, and received full salary or benefits despite the delay. The schools were prepared to adjust curriculum and schedules as needed to uphold rigor depending on whether or not the waiver was granted, so the students were not shortchanged. In spring 2018, the district saw another significant jump in its graduation rate, which has been on the rise in recent years.

Starting in the 2018-19 school year, BHSD will see a significant increase in instructional time over past years at all grade levels, which is beneficial for students and will also provide a greater buffer for future emergency closures or cancellations of school. The incident has also led to a re-examining of the district’s safety plans and protocols, and strengthened its network of regional emergency contacts.

“As fire season stretched on in 2017, our community saw similar situations end in tragedy for communities such as Santa Rosa, California; and Ventura County, California. A year later, we have seen the more than 1,000 homes burn in Redding, Calif., with the Carr Fire. Our hearts are with those communities, as they start their own rebuilding processes after fire. This is an event that people in our community and others are still dealing with emotionally. All schools need better resources to help students deal with the type of terror, trauma and post-traumatic stress produced by an event of this magnitude,” Gallagher said.

Image: New growth emerges after the fire. (Source: Dev Dharm Khalsa/Inciweb).

In the end, the community of Brookings and Harbor was saved. One rural neighborhood burned, but no lives were lost. The “Chetco Bar Fire” burned over 191,000 acres (~279 square miles) and was still only 97% contained by November 1, 2017 after 9+ inches of rain had fallen in the region. The fire will leave a long healing scar, but the most tragic consequences were avoided thanks to the efforts of thousands and a little bit of luck with the weather.

“I hope and pray that something like this is not repeated, but I am fearful it will somewhere, sometime, and somehow. We will take the lessons learned through this ordeal to improve our school district and emergency procedures in the future — and encourage you to take the time to talk with your school community or organization about what you will do when disaster races toward you,” Gallagher said.

About

Sean Gallagher is Superintendent for Brookings-Harbor School District 17C. At the time of this fire, he was starting his 27th year in public education in the State of Oregon. A former high school / community college teacher, high school principal, and 13 years as a Superintendent, he described this event as the most invasive and frightening event to public school district operations and the safety of students, staff, and community that he has ever experienced.

This story was a contribution to the Chetco Bar Fire Series from Sean Gallagher, Superintendent for Brookings-Harbor School District 17C and Nancy Raskauskas-Coons of Brookings Harbor School District 17C.

Opening Image: The sun emerges from the dense smoke plume produced by the Chetco Bar Fire in August 2017 to be visible for just a few minutes over the Pacific Ocean before sunset. (Nancy Raskauskas-Coons/BHSD 17C)